by Kevin R. Kosar

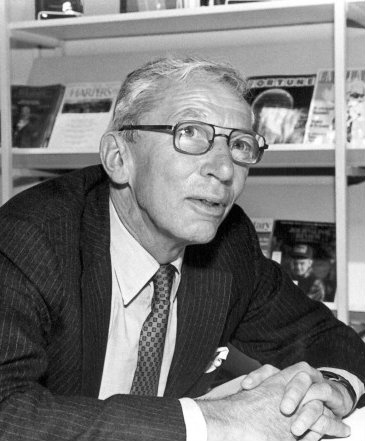

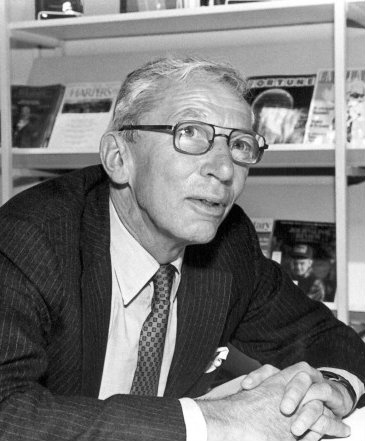

Edward C. Banfield was a political scientist who taught for nearly four decades at the University of Chicago, Harvard University, and the University of Pennsylvania. He served as an adviser to two presidents (Nixon and Reagan) and many lesser officials, and held academic positions, including the vice presidency of the American Political Science Association. Banfield wrote 16 books and scores of articles and essays, which received widespread acclaim and criticism.

The reasons for Banfield’s fame and notoriety are not difficult to discern. For one, he did not write in academese. His prose was crisp, direct, and accessible to anyone with a high school education. This may have been because he began his career as a newspaperman (he would not have used the fancy term “journalist”).

For another, Banfield had little patience for theoretical abstractions. He was rigorous empiricist who believed in evidence. “Facts are facts, however unpleasant, and they have to be faced unblinkingly,” Banfield wrote in The Unheavenly City. Banfield believed that, to understand what people do and why, the social scientist needed to collect data and interview individuals to help put the data in context and analyze and interpret what it meant.

Thus, for example, when he wanted to understand why the people of Chiaromonte, Italy, were so poor, he moved his family there. He interviewed its people, examined them with a psychological test, studied their voting and economic data, and read whatever relevant history he could find. His findings were blunt: it is not the fault of capitalism, a corrupt political class, or some other impersonal cause. The fault lay with the people of Chiaromonte, in particular with their culture. They were poor because they trusted no one outside their families and had no conception of productive social cooperation. This inability to cooperate broadly hobbled political and socioeconomic development. In a typically impish twist, Banfield pointed out that morality—usually construed as conducive to human well-being—was in this instance to blame for Chiaromonte’s backwardness. For its people, moral obligations were powerful but directed exclusively at family members; the world beyond was amoral.

~

The need to pursue the facts wherever they led often put Banfield at odds with the reigning theories and beliefs of the day. James Q. Wilson, his student, friend, and sometimes co-author, wrote that “Ed’s life is an example of that old saying about a prophet without honor in his own country—or at least in his own times”:

[I]n time much of what Ed wrote was accepted by bright people as, slowly and unevenly, they were mugged by reality. In 1955 he and Martin Meyerson published a book about how Chicago built public housing projects. In it they explained that these tall, grim buildings, sited only in areas that guaranteed racial segregation, were a serious mistake. At the time this was a powerful dissent from the view that housing projects must be built and that alternatives—such as supply vouchers to those who needed financial help in renting housing—were unthinkable. Today vouchers are in and some housing projects are being dynamited to remove these eyesores from the city.

Foreign aid programs, Ed later wrote, ignored these profound cultural realities and instead went about persuading other nations to accept large grants to build new physical projects. Few of these projects led to sustained economic growth; indeed, many became a source of money stolen by local political elites. As P. T. Bauer was later to put it, foreign aid was a program whereby poor people in rich countries had their money sent to rich people in poor countries. Where rapid economic growth did occur, as in Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea, foreign aid, to the extent it existed at all, made little difference. Today, scholars now recognize the great importance of culture in explaining why some areas are poor and others prosperous. Only a few of them, however, even refer to Ed’s book. One recent exception is Culture Matters, edited by Samuel P. Huntington and Lawrence Harrison. It was dedicated to Ed.

In 1970, he published his most famous book, The Unheavenly City, in which he argued that the “urban crisis” was misunderstood. Many aspects of the so-called crisis, such as the public’s flight to the suburbs, are not really problems at all, but instead a great improvement in human lives. Some things that are problems, such as traffic congestion, could be managed rather well by putting high peak-hour tolls on key roads and staggering working hours. And those things that are great problems, such as crime, poverty, and racial injustice, exist because we do not know how to end them.

Banfield’s writings often offended the then-popular elite views of individuals as rational and directed by salubrious motives. He had many warm friends and was himself devoted to “the life of the mind,” but his reading of the evidence led him to a view of human nature that was decidedly unromantic. This is not to say that Banfield did not believe in the power of reason—he did. But he agreed with philosopher David Hume’s dictum that for most persons reason usually is “the slave of the passions.” People are parochial and particular—they tend, he found, to concern themselves with the near and the familiar. They tend to flock to those who are like them and often distrust those who are different. Their motives are a mixture of the high and the low. Some pursue long-term goals, while others think scarcely beyond today or even the immediate moment.

The more closely Banfield looked at people and how they behaved, the less confidence he had in government’s ability to improve society through rational planning. Experts, for all their knowledge, also had their own interests and passions. Typically, they operated with limited information that made their analyses flawed, sometimes dangerously so. Indeed, by definition, the more a society cedes decisions to experts, the less democratic it becomes.

~

Banfield’s intellectual interests were broad. The subjects of his books included federal aid to the agrarian poor (Government Project), urban housing policy (Government and Housing in Metropolitan Areas), the sociology of an Italian village (The Moral Basis of a Backward Society), foreign policy (American Foreign Aid Doctrines), and arts policy (The Democratic Muse).

But his work was not scattershot. Banfield’s first book, Government Project (1951), was the seed from which all his subsequent studies grew. The book’s subject was a program to help the rural poor through government planning led by intellectual elites. Itinerant farm workers were invited to join a collective farm in Arizona, where each would have duties and cooperate with one another for the collective good. It was a well-intended New Deal experiment, but it failed miserably. The farmers struggled for power and balked at working with others. Despite being economically better off than they had been, they were unhappy and quit the farm to return to living hand to mouth.

Banfield’s Politics, Planning, and the Public Interest (1955) and Government and Housing in Metropolitan Areas (1958) further developed his critique of government planning. In each instance, Banfield found that urban planners’ efforts to improve housing for the poor were naïve if not dangerous. Their plans took little account of the actual needs and desires of the would-be occupants and were warped by political forces to boot, often with harmful results.

The Moral Basis of a Backward Society (1955) marked Banfield’s return to the topic of poverty. This time, he chose as his subject a poor Italian village, far removed from the American ethos of striving and organizing. The source of the villagers’ poverty was that they were highly family-centric and refused to cooperate (indeed they could not even conceive of cooperating) with others in common enterprises. This discovery, that culture can affect socioeconomic development, was one that Banfield would investigate years later in his studies of urban poverty—most famously, in The Unheavenly City (1970).

Banfield’s studies of urban housing planning stoked his appetite for learning more about the politics and culture of cities. He scaled up—moving from studying small polities (a collective farm and an Italian village) and particular urban policies (housing)—and produced a spate of books just as America’s major cities were erupting in riots: A Report on the Politics of Boston (1960), Urban Government: A Reader in Politics and Administration (1961), Political Influence: A New Theory of Urban Politics (1961), City Politics (1963) Big City Politics (1965), Boston: The Job Ahead (1966), and The Unheavenly City (1970) and its successor The Unheavenly City Revisited (1974). With these books, Banfield provided fresh and arresting explanations of how cities work in practice. They are fantastically complex, organic structures with multiple power centers that drive their actions. Each city has its own systems and its own social structures of class, ethnicity, race, religion, and civic and commercial institutions that divide it and determine how it responds to problems. Politicians are key to cities’ operations. Healthy cities have leaders who avoid taking stark ideological stands on policies and moralizing about right and wrong, who devote themselves to brokering deals between often ruthlessly competing interests, and who are willing to tolerate a little corruption as a price of achieving workable compromises.

No consideration of Banfield’s research would be complete without mention of American Foreign Aid Doctrines (1963), The Democratic Muse (1983), Here the People Rule (1985—a collection of his most important essays), and Civility and Citizenship (1992—a collection of essays by others which he edited and introduced). All four texts plumb questions first pondered in Government Project: What role do experts and elites play in a representative democracy? How do people work together to achieve collective goals? What are the mechanisms of successful self-rule among differing polities? What can the federal government do to improve the lives of the poor?

Although many years have passed since Banfield first considered these subjects, his investigations and findings remain engaging and compelling to this day—not least because they address questions that are fundamental to political life.

Edward C. Banfield was a political scientist who taught for nearly four decades at the University of Chicago, Harvard University, and the University of Pennsylvania. He served as an adviser to two presidents (Nixon and Reagan) and many lesser officials, and held academic positions, including the vice presidency of the American Political Science Association. Banfield wrote 16 books and scores of articles and essays, which received widespread acclaim and criticism….

Banfield’s writings often offended the then-popular elite views of individuals as rational and directed by salubrious motives. He had many warm friends and was himself devoted to “the life of the mind,” but his reading of the evidence led him to a view of human nature that was decidedly unromantic. This is not to say that Banfield did not believe in the power of reason—he did. But he agreed with philosopher David Hume’s dictum that for most persons reason usually is “the slave of the passions”… (Read more at ContemporaryThinkers.org)