“I intend to limit myself to the question: Has two hundred years of the pursuit of happiness left us more happy or less happy? Almost all of those who have pronounced on this question say it has left us more unhappy.”

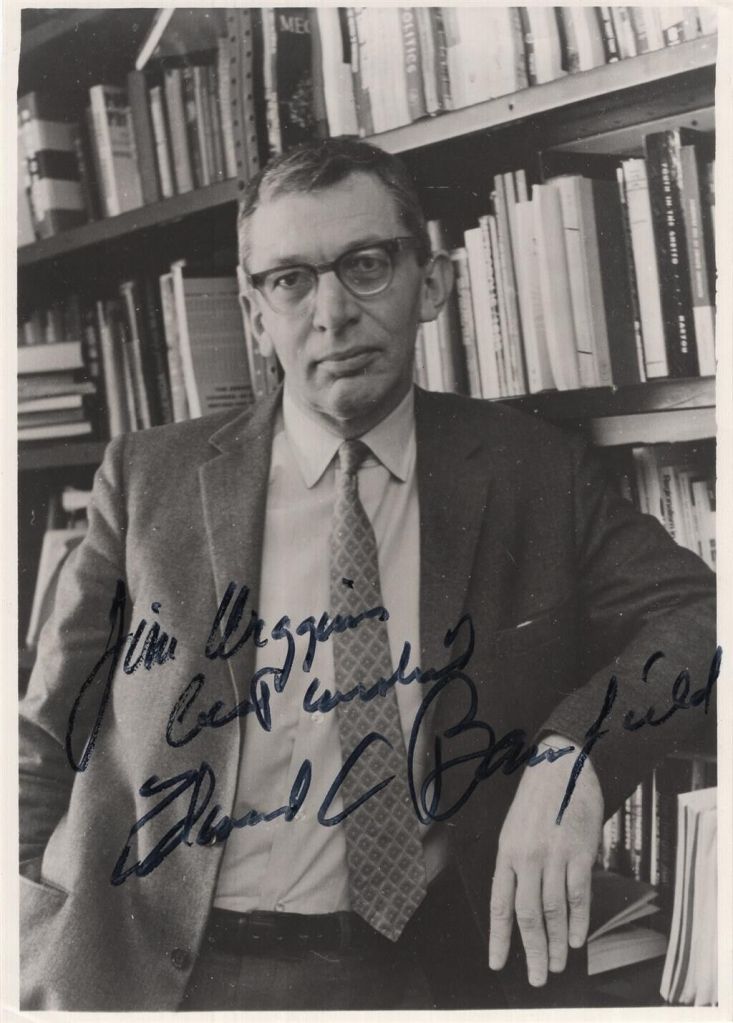

Thus begins Edward C. Banfield’s contribution to this 1988 symposium convened by the American Enterprise Institute (EI). What a gathering: Banfield, Allan Bloom, and Charles Murray, three social scientists who had written best-selling books. They were convened by longtime AEI fellow, Robert Goldwyn, who authored and edited a number of books.

Banfield’s answer to his question is a subtle one, as readers of the symposium will see. But there is no mistaking his disagreement with the various critics left and right who dumped on the American experiment and the notion of limited government and free enterprise.

“Wealth has not prevented America and Americans from being at least as humane and protective of human rights and peace as any society. Indeed, the great calamities that Tocqueville, Solzhenitsyn, and others have spoken of have not eventuated, and what has eventuated has had nothing to do with American wealth. Nazism, Communism, and Muslim fundamentalism were not the results of an excess of material things.”