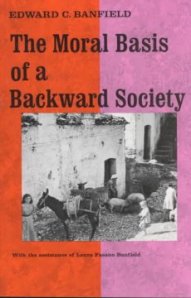

A little over a year ago, the Economist magazine invoked”amoral familism” in the course of explaining the flight of competent, educated Italians from their homeland. These young people, the magazine suggested, were frustrated by the “system of raccomandazioni, or connections (often through families), that rules the [Italian] labour market.” This system is the outgrowth of “amoral familism,” a term Banfield coined in The Moral Basis of a Backward Society to refer to the “the inability [of a community] to act together for their common good or, indeed, for any end transcending the immediate, material interest of the nuclear family.”

A little over a year ago, the Economist magazine invoked”amoral familism” in the course of explaining the flight of competent, educated Italians from their homeland. These young people, the magazine suggested, were frustrated by the “system of raccomandazioni, or connections (often through families), that rules the [Italian] labour market.” This system is the outgrowth of “amoral familism,” a term Banfield coined in The Moral Basis of a Backward Society to refer to the “the inability [of a community] to act together for their common good or, indeed, for any end transcending the immediate, material interest of the nuclear family.”

In the July 1, 2012 Washington Post newspaper, Steve Pearsltein cites amoral familism in explaining Italy’s productivity crisis:

More than in any other of the advanced economies, business in Italy remains family businesses, from the smallest farms and trattoria to some of the largest supermarket chains, industrial groups and fashion houses. Starting companies comes naturally — Italy remains one of the most entrepreneurial countries in the world. But relatively few grow to be very large, and even those that do tend to remain private, relying on family members to fill all key positions and on retained earnings for capital, supplemented by loans from friendly local bankers. Closely related to the distaste for meritocracy and the obsession with family is the weak sense of a civic culture or virtue in Italy….The all-too-common Italian attitude is that while taking responsibility for family is fundamental, beyond that, “What can you do?” This concept of the “amoral family,” first articulated by American political scientist Edward Banfield, may not be surprising for a country that, for 1,500 years after the fall of the Roman empire, was constantly being taken over by one foreign power or feudal state after another. It was perhaps only natural that Italians are inclined to view government as hostile, taxes more like tribute and the court system more an instrument of social control than a source of justice. The problem, however, is that if people don’t expect each other to be fair and honest, if they don’t trust the government or can’t rely on the courts, if they don’t see that their willingness to wait their turn or throw out their trash will be reciprocated by others — then it’s hard to create an economic environment where highly competitive businesses can grow and prosper….(read more)

Banfield’s Moral Basis of a Backward Society was published in 1958; that it still is being cited is indicative of its high quality, and its intuitive appeal as an explanatory hypothesis.